Stood amidst the hallowed ruin of old St Michael’s here in the centre of Coventry you hear the distant drone of the Heinkel He as they careen in the celestial space brooding above your head. So you step inside. You step inside the fevered dreams of our ravaged cathedral. You catch wind of a persistent

thud

thud

thud

you realise is anti-aircraft artillery thundering away on the outskirts of town long dead – the memory of a memory of a memory of a memory.

Nation shall not lift up sword against nation, whispers a sing-song voice in a golden tone, neither shall they learn war any more.

You almost hear the stifle of laughter.

The world begins to lurch beneath you, around and around and around we go, and

the sky!

it is screaming!

oh God is it screaming!

An odd shadow is laid at your feet like a battered funeral wreath, the crooked, broken shape of the holy cross.

Father Forgive.

Father Forgive.

The loping crackle of smouldering timber shimmers in the cool night air.

Here.

Here remain the suffering dead.

Listen and you will hear them, if the night is still.

*

The fate of all explanation is to close one door only to have another fly wide open.

– Charles Fort, The Book of The Damned.

I believe the opening line of Kurt Vonnegut’s anti-war classic, Slaughterhouse-Five, or The Children’s Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death, is a beginning as fitting as I could ever hope to find.

All this happened, more or less.

The sundry importance of those small and humble words will become all the more relevant over the meandering course of the following narrative; all manner of argument, elaboration, proposition and exposition used in order to seek some cohesive axiom, an objective, I have found, much harder to come by than you might think.

It was some six years ago when an author and poet named Jackie Litherland made a somewhat controversial claim in an open letter to The Guardian following the screening of a documentary on the BBC entitled Blitz: The Bombing of Coventry.

The letter’s assertion had been a simple one: the devastating blitzkrieg which had flattened Coventry during the night of November 14th, 1940 (one Jackie Litherland had witnessed as a small child, sat atop her father’s shoulders on the outskirts of Royal Leamington Spa) had not been what the documentary had depicted it to be. That infamous air raid, codenamed Mondscheinsonate by the Nazis’ High Command (we, the citizens of Coventry, simply call it The Blitz), had not been the targeted assault on the city’s numerous engine works and aero accessory factories as was (and remains) the commonly held view. No, this Moonlight Sonata had in fact been an act of callous, calculated and catastrophic revenge precipitated by the Führer of Nazi Germany himself, hatched during the turbulent days that had followed the Nazi Party’s annual rally at the Bürgerbräukeller in Munich on November the 8th, 1940.

Yet it is claim that is the key word here, of course. Any personal involvement the Führer may (or may not) have had in the horrific destruction of Coventry’s medieval heart (and, lest we forget, the tragic deaths of the five hundred and sixty-eight poor souls who burned along with it) is all but lost beyond the veil – imagine a buckshot, on a sign damn near full of them. Now imagine each buckshot to be a representation of yet another little thing we’ll never fucking know.

I have come to discover, in researching this piece, that eternal enigma which has bedevilled the aspiring historian since time immemorial. I have witnessed firsthand this constant quandary which has plagued this fluctuating concept of historicalfact since all this began way back when:

History, at its very core, is as unquantifiable and as intangible as a whisper in the wind.

Our history is rife with all manner of contradiction and absurdity and the inexplicable; phantasmal memories both unseen and unheard. Our history, the English Marxist historian Christopher Hill once wrote, has to be rewritten in every generation, because although the past does not change, the present does; each generation asks new questions of the past and finds new areas of sympathy as it relives different aspects of the experiences of its predecessors. History is broad and mutable, usually little more than the tale agreed between the victorious to be the truth, a fickle potion of theory and fable.

Ah, the truth, a fact or belief that is accepted as true. Marcus Aurelius, last of the Five Good Emperors, once wrote,

Everything we hear is an opinion, not a fact. Everything we see is a perspective, not the truth.

It is from the opinion and the perception of those born and dust through which we desperately scramble in some vain search for the truth, gathering the building blocks of our perceived reality, but even now, as you strike a conversation or open a newspaper or switch on the television or browse the Internet, it should abundantly clear that

everyone

everywhere

has been spinning you a yarn since the day you were born. We live and we breath by the stories that we tell ourselves and one another. We have nothing else.

LISTEN:

What if we are in fact secretly ruled by The Babylonian Brotherhood; a blood-drinking, shape-shifting reptilian race named the Anunnaki hailing from the Alpha Draconis star system?

What if the Brotherhood were broadcasting an artificial sense of self and the world which we humans mistakenly perceive as reality; a holographic experience delivered directly from the Moon, itself an artificial construct (probably a hollowed-out planetoid)?

What if the Illuminati, the Round Table, the Council on Foreign Relations, Chatham House, the Trilateral Commission, the Bilderberg Group, the International Monetary Fund and the United Nations were all Brotherhood created and Brotherhood controlled, along the media and the military, the CIA and Mossad, science and religion and the World Wide Web?

What if George W. Bush and Queen Elizabeth II are in fact satanic paedophiles who feed upon our young?

What if Kris Kristofferson and Boxcar Willie had used the fear and the guilt and the aggression ingrained in our species as an energy source, thus encouraging,

Wars, human genocide, the mass slaughter of animals, sexual perversions which create highly charged negative energy, and black magic ritual and sacrifice which takes place on a scale that will stagger those who have not studied the subject.

What exactly would become of our beloved history if the likes of David Icke ever proved victorious?

This hallucinatory truth which we all so obsess over, which each of us hold in such high high regard? Bent all out of shape; a broken and tired and ancient thing just wheezing away in the corner, convinced it will live forever. The same ol’ patterns of prejudice, fear, discrimination and ignorance have warped and distorted our species and our truth for forever and a day. Our opinions and perceptions are not to be trusted. They never have been.

Some people, usually those desperately scrambling for some blissful illusion of apparent superiority, still live by the abominable Nazi doctrine of ultranationalism, racism, ableism, xenophobia, homophobia and antisemitism; dreaming of a glorious Fourth Reich, idolising Adolf Hitler and his insane Aryan ideal, worshipping at the hellish altar of his abhorrent misdeeds like some bastardised and thuggish priesthood. Can you imagine? People who actively deny that The Holocaust ever happened? What faith can we truly hold in the truth when to some it is so utterly, agonisingly repugnant? Denying the horror we inflict upon ourselves only allows for it to happen again and again and again, from Cambodia to Rwanda to Bosnia.

I am well aware of this morass of contradiction, how one version of the truth can seem so palpable while another an inscrutable nightmare or a whacked out fever dream, yet this is the world on which we live. Any attempt at bringing order to the chaos manifests solely in our own blinkered mind. I am also well aware that in expounding that the vast majority of our planet’s population actually abhor Hitler (and his insane Aryan ideal) I would be at serious risk of stating the blindingly obvious but, hey, I still went ahead and did it anyway. Sure, it may be akin to stating that the rain is wet and the sun is bright but Adolf Hitler, as a man and as an idea, was almost universally loathed during even his own lifetime. He is an object of that strange kind of hatred which will continue to be poked at and lampooned until our small and insignificant world is little more than a burned out, lifeless cinder orbiting a dying star; victim to a vicious satirisation by the eminent Charlie Chaplin in The Great Dictator in the October of 1940, socked in the jaw by the courageous Captain America on the cover of Captain America Comics #1 a full year before the United States even joined the war, constantly belittled in countless YouTube videos concerning everything from being banned from XBox Live to Kanye West’s infamous VMA interruption. Adolf Hitler is now, and may have always been, little more than the walking punchline to some horrible joke.

And it is here where we come around to our second problem with this absurd conception of historical fact: by acknowledging the bias held against Adolf Hitler, I have already proven a failure at providing any real truth in the following piece. Every single piece of information at my disposal will be tarnished by the obvious prejudice that I, along with so many you, hold against him; perverted by that fear and loathing carried along by the collective consciousness. There are horrors in this world, horrors the likes of which we daren’t even dream; a great abyss at the heart of all things. Hitler and Mao and Stalin and Pol Pot, the grand butchers of the 20th Century, must be beyond our understanding save in them we catch some small glimpse of ourselves. Our brains, in some frantic dash to breach its chaotic cognitions, will always force an attempt, however small, at rationalising this grotesque carousal on which we find ourselves lashed.

When we look at Adolf Hitler, we do not see the child whose short life had been blighted by the death of four of his young siblings. When we look at Adolf Hitler, we do not see the small and sickly boy dominated by his disapproving father, a short-tempered, strict and brutal man whose rage Adolf bore for much of his young life. When we look at Adolf Hitler, we do not see the young man who sat vigil at his mothers bedside as she succumbed to breast cancer, the young man who spent hours drawing sketches of her as she lay on her death-bed. When we look at Adolf Hitler, we do not see the destitute artist haunting the slums of Vienna. When we look at Adolf Hitler, we do not see the soldier surviving the muddy, lice infested trenches of World War I.

We see evil.

When we look at Adolf Hitler, we see a culture memory of the devil made flesh. When we look at Adolf Hitler, we seeaone-balled hellbeast born of the most putrid of evil, a sick, degenerate creature dragged howling from void. We see a child conceived at the cusp of the Jack the Ripper killings.

Klara, my darling, what is the matter?

We see the Jewish Quarter drowning in blood. We see sobbing parents and the Angel of Death. We see ghastly premonitions echoing and echoing through time and through space. We see warnings scattered throughout history like

leaves

in

the

wind.

WARNING #1: Führer of the Third Reich, Adolf Hitler, and Napoléon Bonaparte, Emperor of the French, were born 129 years apart. Both men came into prominence during their adopted countries’ existential crisis’, gaining power 129 years apart. These great European conquerors would even declare war on Russia 129 years apart, a miscalculation which would eventually lead to the downfall of both men.

WARNING #2: Osama Bin Laden, founder and former head of the Islamist militant group al-Qaeda, happened to be killed by U.S. Special Forces on the very date that Hitler was believed to have taken his own life in a bunker in the heart of Berlin some sixty-six years before.

They call it Apophenia, the gambler’s fallacy, our painfully human tendency to perceive meaningful patterns within random data. One can find the grand design in anything, the author, novelist, essayist, editor, playwright, poet, futurist, psychologist, self-described agnostic mystic and Discordian Pope Robert Anton Wilson once said, provided the sufficient cleverness.

When you start looking for something you tend to find it. This wouldn’t be like Simon Newcomb, the great astronomer, who wrote a mathematical proof that heavier than air flight was impossible and published it a day before the Wright brothers took off. I’m talking about people who found a pattern in nature and wrote several scientific articles and got it accepted by a large part of the scientific community before it was generally agreed that there was no such pattern, it was all just selective perception.

Yet, I would concede that if someone were to really chew over the mad plethora of literature running loose about the world concerning a certain Adolf Hitler, if someone were to really take in all that sundry and sordid knowledge (perhaps holding it to a certain light), and found nightmarish patterns blossoming in four-dimensional space, it would be at the least understandable. It would simply be a desperate attempt at bringing sense to the senseless.

But Evil, of course, is not an external, supernatural force compelling the hand of mortal men to wickedness. We delude ourselves into thinking so, in some vain effort to keep us separated from them, helping us, paradoxically, to sleep at night. Evil is entirely a philosophical, ethical concept, residing in our collective conscious, invisible, almost illusory. Hitler was not some cackling super villain residing in an underground lair of shark tanks and death rays. Hitler was an elected official, legitimately or not, before becoming leader of a major European power doing what he believed to be right by his people.

Hitler was just a man.

But wait.

Some will assert that another war fit to consume the world had been all but inevitable following the First World War, Hitler or no Hitler. Democracy had tottered between promise and peril in Germany following the end of the monarchy, and The Treaty of Versailles had left a great many with a tireless thirst for revenge. I would be inclined to cast these diversions aside. Hans Frank, Adolf Hitler’s personal lawyer, had spoken of his former employer shortly before hanging at Nuremberg for his complicity in the Nazi crime,

The Führer was a man who was possible in Germany only at that very moment. Had he come, let us say, 10 years later, when the republic was firmly established, it would have been impossible for him. And if he had come 10 years previously, or at any time when there was still the monarchy, he would have gotten nowhere. He came at exactly this terrible transitory period when the monarchy had gone and the republic was not yet secure.

Hitler had seized his moment, cast anchor in the eye of the perfect storm, and plunged Europe full steam into catastrophe by his corrupted actions alone; near enough destroying the city of Coventry, by hook or by crook. The wound Adolf Hitler inflicted on the city’s heart is still felt to this day, still hanging thick and odious in the damp Autumn air, the spectre of a cold night in November is still humming in the fillings of my teeth.

I believe Adolf Hitler to have been in a prison of his own making, to repeat that well-worn phrase, lashed to a seething, poisonous hatred from which he could never truly break free; a schizophrenic wreck, the Americans had decided, incapable of normal human relationships. But I would also keep in mind that history is nothing but a losing game, little more than a backward glance into the unfathomable dark with fingers held aloft. I would keep in mind as you read the following text that all you are actually reading my version of the truth, unquantifiable as it is and as intangible as a whisper in the wind.

*

So. Why Coventry?

November the 9th. It would become one of the most important dates in the Nazi calendar when 1933 rolled around, Hitler finally quenching that thirst for power which had consumed him for so long. November the 9th would come to mark the commencement of celebrations in Munich, Bavaria, the birthplace of the Nazi Party; the commemoration of the Führer’s Beer Hall Putsch, the failed coup attempt of November, 1923.

Munich had been the Hauptstadt der Bewegung, The Capital of the Movement, the spiritual home of the Nazi Party; home to Braune Haus, the Party headquarters, and other Führerbauten which were built around the Königsplatz, the King’s Square. Museums and galleries such as Haus der Deutschen Kunst housed artwork approved by the Führer, and shrines to the attempted putsch which would be used as the scene of lavish memorial ceremonies. The infamous Munich coup attempt, the Beer Hall Putsch, began on the evening of November the 8th at the Bürgerbräukeller, before its impetuous and chaotic end on November the 9th, the Schicksalstag: The Fateful day.

Odd coincidences lay scattered across the length and breadth of the human experience like the fall of Autumn leaves. Coincidence, to quote Roberto Bolaño, obeys no laws and if it does we don’t know what they are. Coincidence, if you’ll permit me the simile, is like the manifestation of God at every moment on our planet. A senseless God making senseless gestures at his senseless creatures.

It was wild and ludicrous coincidence that lead to the horror which befell Coventry on November the 14th, 1940. I would go as far to say that it is the wild and the ludicrous which makes our world go around and around. If you are looking for some grand design amid the chaos I’m afraid you have come to the wrong place.

Permit me, for a moment, an attempt to expound on the ludicrous level of coincidence of which I’m attempting to translate here. Let me tell you about a young man named Gavrilo Princip and his cataclysmic trip to a local café:

On the 28th of June, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, and his wife Duchess Sophie arrived in Sarajevo, Bosnia for a state visit at the behest of Emperor Franz Joseph, predominantly to observe the military maneuvers scheduled for the following days.

The 28th of June had been theirwedding anniversary. Duchess Sophie, a Czech countess, had been treated as a commoner by the Austrian court, and so was only allowed the recognition of the Archduke’s rank when he had been acting in some military capacity. She had specifically joined him on this trip, according to their oldest son, Duke Maximilian, out of fear for her husbands safety.

The reason behind this fear was due to the increasing tensions in Bosnia at this time. Gavrilo Princip was a Bosnian student and a Yugoslav nationalist; a member of a terrorist group known asthe Black Hand, a Slavic independence group angry that Bosnia had been annexed by Austria-Hungary back in 1908. Franz Ferdinand in particular had been an advocate of Austria-Hungary being reorganized by combining the Slavic lands within the Austro-Hungarian empire into a third crown, and had so found himself a particularly popular assassination target.

Gavrilo Princip and five others had been part of a group organised by Danilo Ilić, leader of the Black Hand cell in Sarajevo, to assassinate Franz Ferdinand during his state visit which would happen to fall on the feast of St. Vitus, a Serbian national and religious holiday commemorating the 1389 Battle of Kosovo against the Ottomans, at which the Sultan was assassinated in his tent by a Serb.

Upon their arrival in Sarajevo, Franz and his wife had travelled through the tumultuous streets as part of a motorcade, along with Governor Oskar Potiorek and other dignitaries. Their first stop on their preannounced program was a brief inspection of a military barracks and it was during thatjourney that Nedeljko Cabrinovic, a member of Gavrilo Princip’s group, threw a grenade at the passing Archduke.

The bomb bounced off the car’s folded back convertible cover and out onto the street, finally exploding beneath another car in Ferdinand’sentourage; leaving around sixteen people, including an Austrian officer, injured.

Princip and the rest of the group dispersed in the enduring chaos.

Cabrinovic took a cyanide pill which failed to kill him, inducing only vomiting, and so jumped into the river Miljacka in order to drown himself. Yet the river, due to the hot, dry summer, was only 13 cm deep. Police dragged Čabrinović out of the river where he was severely beaten by the baying crowd before finally being taken into custody.

A furious Ferdinand insisted on travelling to the hospital in order to visit those injured in the grenade attack but, unfortunately, his driver had not fully understand the instructions and promptly found himself lost.

Stopping to check where he was, the driver attempted to reverse back out on to the Main Street, where by some unimaginable bad luck, he stopped at the feet of Gavrilo Princip who had just left Moritz Schiller’s café.

Princip, likely bewildered and beatific on such a tide of good fortune, grabbed his pistol and opened fire.

Bang.

Bang.

Bang.

It took just a single bullet fired by a single teenager to ignite the cinder from which leapt the frightful flames of war.

A teenager, who had just happened to step out of a café at just the right moment in a stroke of dumbfounded luck, changed the world irrevocably.

Archduke Franz Ferdinand bleeding to death on a Sarajevo street and the diplomatic crisis that ensued inevitably lead to The Great War; four years, three months and two days of bloody trench warfare which left some seventeen million dead.

The Great Depression followed in 1929 which would eventually lead to a desperate Germany electing Hitler as their leader and, within a few short years, World War Two broke out; a war which only ended when two atomic bombs were dropped on Japan in the August of 1945.

This first and only use of nuclear weaponry during warfare lead to forty-four years of the so-called Cold War between the USSR and the US; almost leading the Earth up the path to total destruction on innumerable occasions.

Proxy wars, such as those in Korea, Vietnam and Afghanistan, began to explode across the globe, supported by the twosides.

Crash.

Boom.

Pow.

The Munich Putsch would share a date with many key events in Germany’s recent history, each connected by restless causality; each to occur on The Fateful day.

The execution of the liberal leader Robert Blum, who had been arrested following the Vienna revolts, occurred on the November 9th of 1848. His premature death had effectively brought the March Revolution, a series of violent uprisings across Europe striving for economic and political change, to an end with a single bullet.

Bang.

It also marked the day the German monarchy was finally abolished, the day Kaiser Wilhelm II was dethroned by his chancellor Max von Baden following the November Revolution of 1918, the result of a country weary of war, and above all hungry, again giving in to rebellion.

The Hitlerputsch would also come to share an anniversary with the Night of Broken Glass, one the bloodiest nights of the Nazis’ wild rise to power; the appalling antisemitic pogrome of November 9th, 1938, in which some four hundred people died over the course of a single bloody night.

And November 9th would eventually mark the triumphant day the Berlin Wall fell after a series of radical political changes throughout the Eastern Bloc effectively brought the storied chapter of communism in Eastern Europe to a close.

The seismic change brought upon the very fabric of German society by these events are still felt today the whole world over, the aftershocks still throbbing away like some subterranean techno beat.

November the 9th made the whole world shake.

Around and around and around we go.

It was the possibility of darkness that made the day seem so bright.

– Stephen King, Wolves of the Calla.

*

Storm! Storm! Storm!

The serpent, the dragon from hell has broken loose!

Stupidities and lies his chains have burst asunder,

Lust for gold in the dreadful couch,

Red as with blood are the heavens in flames,

The roof-tops collapsed, a sight to appal.

One after another, the chapel goes too!

Howling with rage the dragon dashes it to pieces!

Ring out the assault now or never!

Germany awake!

– Dietrich Eckart, Storm Song.

Had it been the death knell of German power and prestige following the devastating loss of The Great War and The Treaty of Versailles which led to such wild abundance of right-wing political parties springing up across Bavaria or had it been just another well from which those broken men could quench their thirst for violence?

Some would claim it had been an act of divine prophecy.

With each party trumpeting their own trivial brand of the grand nationalist cause, it was in the Bavarian capital of Munich where the Nazi and their brethren found themselves the perfect safe haven, just far enough away from the capital of Berlin to avoid any unwanted attention without isolating themselves from the wider German population.

Hitler, having remained in the army following the end of the war, had been ordered to infiltrate what had then been named the German Workers’ Party when in the employ of the Bavarian Reichswehr, the newly formed Weimar Republic‘s military organisation, in order to monitor the party’s activities. Hitler quickly became infatuated with the party founder Anton Drexler’s anti-Semitic, nationalist, anti-capitalist and anti-Marxist rhetoric, becoming a member of the party at Drexler’s request on the 12th of September, 1919.

The journalist, playwright, poet, and politician Dietrich Eckart, one of the burgeoning party’s main sponsors, had been heavily involved with the esoteric Thule Society, named after the mythical northern country of Greek legend, and a keen admirer of the occultist Helena Blavatsky, who had co-founded the Theosophical Society back in 1875.

Blavatsky had argued in her book, The Secret Doctrine, that humanity had descended from a series of what she had termed the Root Races; ancient races who had once existed on the lost continents of myth and legend. Blavatsky named the fifth of these races the Aryan:

The Aryan races, for instance, now varying from dark brown, almost black, red-brown-yellow, down to the whitest creamy colour, are yet all of one and the same stock – the Fifth Root Race – and spring from one single progenitor, who is said to have lived over 18,000,000 years ago, and also 850,000 years ago at the time of the sinking of the last remnants of the great continent of Atlantis.

Blavatsky would also go on to claim that there were certain modern (non-Aryan) peoples who were intrinsically inferior to the Aryans. She would regularly contrast Aryan culture with Semitic culture, most often to the latter’s detriment, asserting that the Semitic people were an offshoot of the Aryan race who had become, she said, degenerate in spirituality and perfected in materiality. Blavatsky would also state that some peoples were little more than semi-animal creatures. She gave the Tasmanians, a portion of the Australians and a mountain tribe in China as her chief examples.

Blavatsky, it might seem, lived with some terrible truth.

Blavatsky had been a key influence on the blossoming Thule Society; in 1917 those who had wanted to join had been obliged to sign the following requisite, a special blood declaration of faith concerning their lineage:

The signer hereby swears to the best of his knowledge and belief that no Jewish or coloured blood flows in either his or in his wife’s veins, and that among their ancestors are no members of the coloured races.

Eckart may have been the one to provide that esoteric edge when the Nazi Party began establishing the theories and beliefs during its embryonic stage; introducing Hitler to Blavatsky’s idea of the Aryan race and to The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the antisemitic hoax which purported a Jewish plan for global domination, this whirlwind of uncanny influence proving prime fuel for Hitler’s hungry mind.

Eckart had perhaps been under the (admittedly odd) impression that Hitler was this German Messiah whose arrival the Thule Society had believed to be imminent; the prophesied redeemer of German power and prestige following the devastation after The Great War, theGreat One, theNameless One, whom all can sense but no one saw.

Perhaps Hitler had thought this too, drunk on his own grandeur. When in a bid to increase the party’s appeal, the German Workers’ Party renamed themselves the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, with Hitler designing the party’s infamous banner, the mystical swastika in a white circle on a red background:

Hitler would later describe it as a race emblem of Germanism, those revered colors expressive of our homage to the glorious past and which once brought so much honor to the German nation.

Eckart would die in the December of 1923 an alcoholic and morphine addict, the Nazi Party claiming his death was the result of police brutality following the Munich Putsch but Dietrich left this world by product of a heart attack, purportedly leaving these final words:

Hitler will dance but it is I who have called the tune!

I have initiated him into the Secret Doctrine, opened his centres of vision and given him the means to communicate with the Powers. Do not mourn for me: I shall have influenced History more than any other German…

*

Many members of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party had been ex-soldiers like Hitler, angry at the insistence of the Weimar Republic (the federal republic established in 1919 to replace the German Empire) for paying the reparations demanded of them by the aforementioned Versailles treaty. In the eyes of the nationalists this was an admittance of guilt for starting the First World War by a government widely seen as a morass of corruption, degeneracy, national humiliation and ruthless persecution of the honest national opposition.

Among the Nazis’ number had been a retired Quartermaster General named Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff, who had settled in Bavaria following The Great War, when the German Empire he had served so valiantly for so long had ceased to exist.

Ludendorff, poor Ludendorff, was just another miserable fool among many with unfortunate trait the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer would have described as having nothing at all of which he can be proud, adopting as a last resource pride in the nation to which he belongs; ready and happy to defend all its faults and follies tooth and nail, thus reimbursing himself for his own inferiority, easily sucked in by that early, fanatical rhetoric being spouted by Hitler in the crowded beer halls of Munich, spewing rowdy polemic against the Treaty of Versailles, his rival politicians and especially the Marxists and the Jews.

Ludendorff had been a recipient of both the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross and the Pour le Mérite for his courageous efforts during the war but left downcast and bitter by the chaotic events of the following years; convinced (or so he claimed, and all we have are claims) that the German Army had fought a wholly defensive war, that his country had been betrayed by both the Marxists and the Republicans in the signing of the Versailles Treaty and had been disgusted by the actions of the Triple Entente (the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland) who he believed had not only have been the aggressors of that First World War but also determined to dismantle Germany in its entirety,

By the Revolution the Germans have made themselves pariahs among the nations, incapable of winning allies, helots in the service of foreigners and foreign capital, and deprived of all self-respect. In twenty years’ time, the German people will curse the parties who now boast of having made the Revolution.

Ludendorff was also a chief proponent of both the stab-in-the-back myth (Dolchstoßlegende), the deluded conviction that the German Army did not lose World War I but were instead betrayed by civilians on the home front (an historical fact the Nazis made an integral part of their official history of the 1920s), and of Total War; believing, rather pessimistically, that peace was merely the boring lull between civilisations’ frequent and unusually determined attempts at bloody suicide.

In his book, Der Totale Krieg, published in 1935, Ludendorff stated that the entire physical and moral forces of a nation should be mobilised during wartime; a sentiment the Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels was later more than happy to exult during his Sportpalast speech on the 18th of February, 1943, when the tide of the war had turned against Germany and its Axis allies, Italy and Japan,

Do you believe with the Führer and us in the final total victory of the German people? Are you and the German people willing to work, if the Führer orders, 10, 12 and if necessary 14 hours a day and to give everything for victory? Do you want total war? If necessary, do you want a war more total and radical than anything that we can even imagine today?

Yet complicating matters, Ludendorff was also a pagan worshiper of the Nordic God Wotan, the Allfather and Master of Ecstasy, a God of both war and poetry, divine patron of both rulers and outcasts.

Wotan was an enigmatic and complex figure, prone to long, solitary wanderings throughout the cosmos on self-interested quests, a relentless seeker and giver of wisdom but with little regard for such communal values as justice, fairness or respect for law and convention. While worshipped by those in search of prestige and honour and nobility, Wotan was often cursed for being nothing but a fickle trickster like his son, Loki.

That a man such as Ludendorff would have worshipped a God such as Wotan (whose prominent transgender qualities would have brought unspeakable shame to any Germanic warrior) and that the Nazis would eventually use such significant amounts of Norse symbolism in their propaganda, does much to show the inherent contradictions in their philosophy.

In only worshipping the Gods of their ancestors, or those pertaining to the culture in which they were raised, they made some misguided attempt at remaining the pure Aryan specimen Hitler so often espoused, but the Nordic religions had held very little influence on the core of their loathsome beliefs.

I suppose that it would be easy to assume that all Hitler had ever wanted was total and unmitigated power and very little else; the host of arcane imagery he would later make use of, the Nordic Gods and the mystical swastika and the fantastical Jewish conspiracies, it was all merely a means to an end.

I suppose it would be easy to assume that Hitler’s primary goal, this vision of the future which he so often extolled to the frenzied and brainwashed masses, the grand design of an Aryan master race and it’s Thousand Year Reich, it was all little more than the stepping-stones leading to his utter supremacy of the globe.

Perhaps Hitler, in that aforementioned prison of his own making, had lashed unto such an inexplicable hatred for anyone he’d deemed inferior (the Untermensch) as an anchor, save he lose himself in the wreckage of his broken mind. The hatred of the Jewish and the homosexual and the disabled and the Romani that he carried like a millstone around his feeble, damaged neck, had simply been a warped act of kicking out at a world he felt had so often hurt and betrayed him, from his days as a destitute artist living in Vienna to those weak and fearful politicians in Berlin who had stabbed him and his country in the back following the German surrender of 1918, a small and bitter man who would never allow his father to hurt or betray him again.

Perhaps every death in those terrible years that followed the Beer Hall Putsch, all those countless lives that would be torn asunder, perhaps they were little more than the bitter aftereffects of an extreme and deranged act of self-preservation.

Perhaps, as writer of this piece, I should know better. Any attempt at reaching an understanding as to the true motivations of Adolf Hitler (or anyone, for that matter) is akin to teaching a cow the rules of dominoes: it’s inane, it’s exhausting and it’s more than a little ridiculous.

And perhaps, as writer of this piece, I would refuse Adolf Hitler the small victory of acknowledging his abhorrent accomplishments by instead belittling a small and bitter man who did, through sheer force of will, change the course of human history.

It was in 1923 when that course began to change. It was in 1923 when Hitler would arrive upon the fateful day.

The long march toward Coventry’s destruction edged on.

*

It was in the November of 1923 when the fledging Nazi Party had found itself fired into action by Il Duce Benito Mussolini’s successful March on Rome the previous year.

Hitler had felt the compulsion to act for some time, lest his followers turn to the Communists or the Marxists or anyone else who may have seemed to carry an answer to Germany’s woes, and it was not before long that the Nazis found themselves carried along on some wave of delusion, sure in their belief that by overthrowing the Bavarian government, based in Munich, they could use the city as a power base for their march against the Berlin Jew government and the November criminals of 1918. As Nietzsche once noted,

Madness is something rare in individuals – but in groups, parties, peoples, and ages, it is the rule.

And it was on the evening of November 8th that Hitler, along with six hundred of his men, stormed a meeting being held at the infamous beer hall, Bürgerbräukeller, by the Bavarian Prime Minister Gustav Ritter von Kahr, joyously declaring,

The national revolution has broken out! The hall is surrounded!

Threats were delivered to Kahr and his men. Allegiances were presumably declared. Anger and tension and no little confusion simmered in the cool night air. Speeches were made to the Nazis’ now captive audience.

When Hitler spoke, Karl Friedrich Max von Müller would later describe, it was a rhetorical masterpiece. In fact, in a few sentences he totally transformed the mood of the audience. I have rarely experienced anything like it.

Yet with a mere two thousand men at his command, Hitler had placed much of his hope in the people of Munich rising up and joining him in the heroic crusade against such a dishonourable government but this support from the masses never quite materialised.

It was on the following morning, November the 9th, when The Beer Hall Putsch erupted into violence. For want of a better plan, the Nazis’ had marched on the centre of Munich, led by Hitler and Ludendorff, coming to an impasse with the waiting police who would not allow them passage at the Residenzstraße.

And the situation, as they are wont to do, quickly erupted with a

bang

bang

(click)

bang.

The ensuing chaos left sixteen Nazis’ dead.

Hitler dislocated his shoulder at some point during the ensuing fighting, either by running for cover when the bullets started flying or by heroically catching a mortally wounded comrade in his arms, I’m afraid we will never know.

But what we do know is that Hitler would eventually make his escape, making a run for a yellow car which had been ordered to wait for him a street or two away; leaving Ludendorff and many more of his loyal men to be arrested in Munich’s main square.

So it goes.

Adolf Hitler could have so easily died on that day. Adolf Hitler could so easily have become another lonely martyr for a battle soon forgotten, could have so easily bled out on those cold streets of Munich on a miserable November morning; the arch-villain of the 20th Century reduced to a buckshot piece of shattered meat scattered among the cobbles.

How different a world would it have been had Hitler done the decent thing that morning and taken a terminal slug to the heart or the brain?

I often wonder how the police dispatched that day had felt after the fact. I often wonder of that one man who must have come so close to killing one of the great monsters of human history. Had he been one of the four policemen who were killed in the ensuring violence that engulfed Munich that day, I wonder, or had he the misfortune to live long enough to see Adolf and his followers bring about the war to end all wars, no end of horror and misery and pain, right atop his country’s head?

Hitler found himself arrested and charged with treason a mere two days later and following a twenty-four day trial, which would be covered extensively in the newspapers of the day, he was found guilty and sentenced to five years imprisonment in a Bavarian fortress named Landsberg.

While all of this may have seemed very much like a humiliating defeat for the burgeoning Nazi Party (and humiliating it was), the trial had at least brought Hitler and his increasingly rampant nationalist sentiment directly into the public consciousness.

I would suppose, when seen to have had a bona fide war hero such as Ludendorff at his side during that disastrous march on Munich, Hitler may well have, at the very least, been regarded as something of a tragic figure, dragged to his knees by the Jews, Marxists, and cultural Bolsheviks who ran the Republic.

Perhaps.

Hitler dictated his literary disasterpiece and future manifesto Mein Kampf to his fellow prisoner and future Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess during his short stay within the confines of Landsberg (this before his early release for good behaviour some eight months later); dedicating the text to the sixteen valiant men who had died for the Nazi cause on that cold morning in Munich and to his old friend Eckart.

Along with some repellent political theory and a little bleeding-heart autobiography, Hitler regurgitated that grand Jewish conspiracy to gain world leadership line which Eckart had shared some three years previous, that hallucinatory conspiracy he and only he could stop.

Levi Salomon, a spokesman for the Berlin-based Jewish Forum for Democracy and Against Anti-Semitism, would later go on to describe the book as outside of human logic, which is an evaluation, as much as I might try, I have no hope of ever improving upon.

Rudolf Hess would go on to become Deputy of the Führer when Hitler finally seized power but would feel increasingly sidelined in the years that had followed, distanced from the affairs of the nation following the outbreak of war and effectively usurped by Martin Bormann, head of the Parteikanzlei, as one of Hitler’s closest aides and confidants.

It was on the 10th of May, 1941, when Hess, showing particular foresight in his concern that the looming invasion of the Soviet Union would lead to a war on two fronts Germany had no chance of winning, flew to Scotland in a clandestine mission of his own devising, a misguided attempt at negotiating peace with the United Kingdom.

This did not end well for him as these things rarely do. Hess would never taste sweet freedom again.

It was at the Nuremberg Trials some five years later, after the war had come to an explosive end in Japan and Hitler had finally bit that bullet, where Hess was found guilty on two counts: crimes against peace (planning and preparing a war of aggression) and conspiracy, with other German leaders, to commit crimes.

He received a life sentence.

A half-dozen suicide attempts followed throughout his long and lonely life, the occasional visit from his family the only glimmer of hope in an increasingly torrid existence. He had become a ghost.

Hess finally gained his freedom at the grand old age of ninety-three, hanging himself in the summer-house built in the gardens of Spandau Prison. What would Vonnegut have said?

So it goes.

*

I have struggled with bouts of depression for most of my adult life.

The feeling that the illness invokes is perhaps beyond my skill as a writer to adequately explain, an indescribable sensation of sadness and hopelessness and loneliness, invasive like a cancer; trapped in a burning house with no hope of escape.

Nobody ever mentions the psychical symptoms. They come as quite the surprise. I will often start the day with explosive diarrhoea when the clouds roll in, wave after vicious wave of deafening nausea shuddering through my frame like Sisyphus’ boulder. A tiredness settles in on your aching bones; you can almost hear the lights as they go out, one by one:

Goodbye, sex drive!

So long, healthy appetite!

Adiós, self-esteem!

Everything, from the golden sun in the azure sky to the zoetic dirt rich beneath your feet; it is all so fucking unbearable.

And then it is gone. Life is returned, with a beautiful smile.

You may wonder why I am telling you this. You may ponder the correlation this may have to The Blitz.

I had lived on Geoffrey Close in the suburb of Wyken as a young child, a small cul-de-sac lined with trees which always seemed in blossom. The sky had always felt brighter and the sun had always felt warmer. It’s memory glows brighter with every passing year.

We had a neighbour named Freda when we lived on Geoffrey Close. Freda had seemed almost impossibly old and wise beyond words, with a kindness that seemed almost impossible to bare. She would teach us, my sister and I, the utmost importance in reading; the host of knowledge and magic which lay in wait within each tome. She would regale us with the screwball tale of the first plane to have crossed the skies above Coventry; the pilots’ legs, dangling out into the wild blue yonder, gliding above her head.

Freda would often reminisce on The Blitz, when she had been a young mother shadowed by an unforgiving sky. She once told us of The Burges the day after it had happened, once a vibrant thoroughfare with enviable footfall; now home to pawnbrokers, bookmakers and pay-day loan shops. She had told us how the River Sherbourne, having flowed in seclusion beneath for generations, had been thick with blood, an open artery of a dying city. That sight, she said, had brought it all home.

I have a theory (which, remember, is all we’ll ever have) that the city of Coventry, every street and every structure, is suffering from what can only be described as a severe depression.

I am well aware how crazy this must sound. Coventry is merely a city, a complex system of sanitation and utilities and land usage and housing and transportation, bound to a name so ancient all meaning has since vanished, yet the Moonlight Sonata, such a beautiful title, it is still haunting her; a barbaric phantasm still stirring in the earth. Listen and you will hear, if the night is still.

What I have written, thus far, is a misguided attempt at providing some sense to the senseless, charting the course that lead to the inevitable. Coventry burned and that will remain forever so.

Time is no un-troublesome route, a passage from which a map can be wrought. Time is an ocean, blacker than sin, each of us condemned to be lost to its tide, sooner rather than later.

Yet, we must try, mustn’t we? We must try as we might to find a way through.

*

Hitler and his Nazi Party eventually gained power on the 30th of January, 1933, after the years of struggle, the Kampfjahren, a decade of conniving and colluding and bloody bloody violence, when the President of the Weimar Republic, Paul von Hindenburg, appointed Hitler Chancellor.

An arson attack on the German parliament in the March of that year, the Reichstagfire, had been determined as the first stirrings of a Communist revolution and so, with Hitler’s urging, Hindenburg signed into law the Reichstag Fire Decree, suspending all civil liberties in Germany in order to root out the instigators.

Piece by piece, it had all been falling into place for Adolf Hitler. The consequent Enabling Act, which had been signed on the 24th of March, 1933, through bullying and coercion, dispensed with Germany’s constitution and its electoral system entirely, effectively making the country a one-party state with Hitler as its leader.

Hitler had finally attained that absolute control he had sought for so long.

Hitler soon quit the League of Nations and had introduced military conscription by 1935 (thus violating their hated Treaty of Versailles), dispensing with his long list of enemies on The Night of the Long Knives. He beat and he beat on that ol’ drum of war; first occupying the Sudetenland before Czechoslovakia and Poland and Finland and Denmark and Norway and France and Belgium and Luxembourg and the Netherlands and Holland all fell away like dominos.

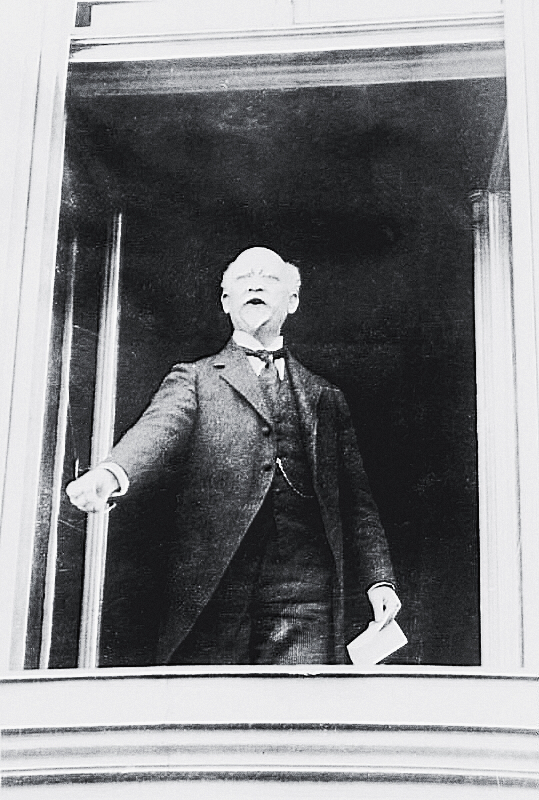

When total and utter victory had seemed a mere whisper away, Hitler made a fateful speech in the very heartland of his party. He stood before an enraptured crowd at the very spot where it had all began. He stood in the Munich Beer Hall, the Bürgerbräukeller, on the night of November 8th 1940 (the same hall in which he had narrowly avoided an assassination attempt the previous year), and made a speech, a speech that had found him in a particularly defiant mood,

A year ago, as I mentioned earlier, Poland was eliminated. And thus we thwarted their plans a first time. I was able to refer to this great success on November 8, 1939. Today, one year later, I have further successes to report! This, first and foremost, only he who himself served as a soldier in the Great War, can appreciate fully as he knows what it means not only to crush the entire West within a few weeks, but also to take possession of Norway up to the North Cape, from where a front is drawn today from Kirkenes down to the Spanish border.

All the hopes of the British warmongers were then torn asunder. For they had intended to wage war on the periphery, to cut off the German vital lines, and slowly strangle us. The reverse has come true! This continent is slowly mobilizing, in reflecting upon itself, against the enemy of the continent. Within a few months, Germany has given actual freedom to this continent. The British attempt to Balkanize Europe (and of this the British statesmen should take note) has been thwarted and has ended! England wanted to disorganize Europe. Germany and Italy will organize Europe.

Now in England they may declare that the war is going on, but I am completely indifferent to this. It will go on until we end it! And we will end it, of this they can be sure! And it will end in our victory! That you can believe! I realize one thing. If I had stepped up as a prophet on January 1 of this year to explain to the English: by the spring of this year, we will have ruined your plan in Norway, and it will not be you in Norway, but Germany; in the summer of this same year you will no longer be in the Netherlands or come to the Netherlands, but we will have occupied it; in the same summer you will not have advanced through Belgium to the German borders, but we will be at yours; and if I had said: by this summer, there will be no more France; then, all would have said: The man is insane. And so I shall cease from making any further prophecies today…

It was within a few short hours of this triumphant speech that the RAF had dropped their bombs on Munich, birthplace of the movement, and the fate of Coventry was sealed.

Crash.

Boom.

Pow.

It was also proof, I would propose, that the Universe does have a sense a humour, albeit a very morbid one.

Imagine, for a moment, how Hitler must have felt as Munich burned around him. He had narrowly avoided a bloody death in the city of Munich for the second year in a row and for a third time in his fifty-two years on this Earth. How powerful he must have felt, how invincible! He had even survived the dreaded Western Front, once took shrapnel to the leg, once blinded by the gas.

Death must have seemed little more than a fate for the others. Hitler must have felt a God.

Likely loaded on a cocktail of rat poison, amphetamines, bull semen and morphine provided by his obese physician Dr Theodor Morell, with just a little powdered cocaine to clear his sinuses and soothe his throat, however omnipresent he may have felt, the Führer was still very very hungry for revenge; a revenge that would lead to an exerted effort to entirely remove from existence the medieval city centre of Coventry as a demonstration of his ruthlessness and insane power.

A Moonlight Sonata.

*

Memory is of no use to the remembered, only to those who remember. We build ourselves with memory and console ourselves with memory.

– Laurent Binet, HHhH.

A single choice.

A single choice can bring the world down its knees.

An unscheduled stop at a busy café or by simply becoming member 505 of a small nationalist political party in Bavaria can wreak consequences almost unimaginable.

You simply drop a pebble into the ocean and you watch the ripples as they grow.

My Grandfather Tom was stood amongst the ruins of an Italian hospital, the bitter sun beating down on his haggard head. American warplanes cast their vicious shadow on all those who had stood beneath, those men who had desperately scrambled amongst a smouldering wreckage for any sign of existence.

The first Tom, his brother Tom, had been lost out on the Western Front, along with so many others like him, years before; each consigned to memory, unprepared for the brutality humanity inflict upon one another.

My Grandfather Tom, I think, felt some guilt for all that; an ineffable weight on the cusp his psyche, a shameful and cancerous guilt of having to carry the name of a brother he had been doomed to never meet, all on the account of a fateful choice made years before he had even been born. I think he may have even felt some guilt for even making it this far, stood on the sun-bleached hospital which was now little more than a broiling ruin.

In the rubble at his feet lay a small child of no more than a few days old, a child who now too had been consigned to that realm of memory. A child whose life had been dashed away by the cruel and unforgiving hand of a distant God.

Somebody whistled I Don’t Want to Set the World On Fire in the distance as he spotted another child, its limp and broken arms reaching out to a world which seemed devoid of any rational thought or empathy.

A world at risk of losing itself.

I will not even begin to attempt a description of how my Grandfather must have felt in those moments. They fall far beyond the use of mere words. These were moments, I’m sure, he had been doomed to repeat.

He had spotted yet another child as a siren sounded somewhere out in the distance, the ripples now becoming vast waves. My mother placed me into my cot and took a glance out of the window, Two Tribes straining from the drowning radio. The sky, it seemed, was screaming; a terrible and mournful sound in possession of an impossible recollection.

In the wake of that heartbreaking wail the trees out on the Geoffrey Close seemed to refrain from their usual playful dance. The birds assumed a vow of silence and hid amongst the bushes. The street my mother had called home mere moments before seemed devoid of

the joy

the sorrow

the laughter

the fear

the passion

the pain

the lives upon lives ingrained in the very bones of this land.

It all seemed little more than a nihilistic nightmare, the screaming abyss, empty and meaningless and blacker than black.

And then the siren was gone.

*

Why do we argue? Life’s so fragile, a successful virus clinging to a speck of mud, suspended in endless nothing.

– Alan Moore, Watchmen.

If the cataclysmic destruction of medieval Coventry on the moonlit night of November 14th, 1940, had not been for any tactical benefit but indeed a determined and concentrated effort to destroy what had been widely described one of the finest medieval cities in Europe then the Coventry Blitz had been a precursor to the so-called Baedeker Blitz.

Paul Joseph Goebbels, the Reich Minister of Propaganda, had disliked that title. He preferred to describe the Nazis’ raids on English cities such as York and Canterbury (chosen not for any military value but due to their cultural or historical significance selected using the eponymous travel guides) as terror bombings, while equally keen to encourage the idea that these German efforts had merely been retaliatory measures.

And yet, for all this indecisiveness on how best to describe the Baedeker Blitz, the end result had remained resolutely the same: the targeted destruction of English heritage.

At the dawn of the Second World War, Coventry had fast become a thriving industrial city of around 238,000 people, home to all manner metal-working industries; such as cars, bicycles, aeroplane engines and, since around 1900, numerous munitions factories. It had been therefore, or at least according to the historian Frederick Taylor, a legitimate target for aerial bombing.

Legitimate.

Legitimate.

Legitimate.

Just try to swallow that for a moment.

Here we find another problem with this mythical and nonsensical historical fact: just how it easy it becomes to channel the like of Joseph Stalin, the death of one man is a tragedy, the death of millions is a statistic. How easy it becomes to lose sight of the miracle of life, how easy it becomes for a death, any death, to lose all sense of meaning.

The Second World War had not merely been a series of catastrophic military encounters at this point. It had been far worse than all that. The war, by its bitter end, had left some sixty million dead and countless more displaced.

The pale blue dot we call home, it must have seemed little more than a grand chessboard on which to battle their wits to Hitler and Churchill and Stalin and the rest, Roosevelt, Mussolini, Hirohito and Kai-shek, yet in the face of fields littered with bones of our dead, in the face of great burial pits still teeming with those desperately clinging to life, in the face of such inconceivable and mind numbing horror, the human race had begun losing all semblance of its humanity.

As Tokyo and Coventry and Dresden burned beneath cataclysmic firestorms, as Hiroshima and Nagasaki vanished beneath the horrifying power of weapons-grade uranium, now, I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds, our collective history was becoming little more than

Coventry felt that first lick of the flames that had near engulfed continental Europe during the Battle of Britain. Some one hundred and ninety-eight tonnes of explosive fell on the city between August and October, 1940, leaving one hundred and ninety-six people dead and nearly seven hundred injured; the newly refurbished Rex Cinema going kablooey proof even Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh were not safe from the vile Nazis’ fury.

A Second Lieutenant named Alexander Fraser Campbell of the Royal Engineers, 9th Bomb Disposal Company, was awarded a posthumous George Cross for conspicuous gallantry during this time, having successfully helped in the frenzied war effort by being rid of an unexploded bomb which had fallen at the Triumph Engineering Company‘s works over in Canley, shutting down the production lines at two of its neighbouring factories.

Campbell, along with Sergeant Michael Gibson, Sappers W. Gibson, R. Gilchrest, A. Plumb and R.W. Skelton and Driver E.F.G. Taylor, spent four long days uncovering the bomb from beneath the mess of rubble and debris before coming to the realisation that the device contained a very damaged delayed-action fuse mechanism which could not be removed in its original place. The squad were forced to load the two hundred and fifty kilogram bomb atop a lorry where it was taken to Whitley Common and remotely detonated.

Kaboom.

Campbell, in an act of extraordinary (some might say suicidal) bravery, had positioned himself alongside the bomb during that journey, listening intently for any timer mechanism that may have been activated by the bomb’s removal.

Tick.

Tock.

Tick.

Tock.

Campbell would die the next day, along with his entire squad, whilst dealing with another bomb out on the Whitley Common.

So it goes.

*

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

– W. B. Yeats, The Second Coming.

Every cat in the city was said to have vanished over night in the days before the raid, perhaps aware of some spectral caveat, some sulphuric stench of blood and death and misery that hung in the air like an executioner’s axe.

In the year prior to the outbreak of The Great War, Swiss psychiatrist and psychotherapist Carl Jung had been plagued with similar visions, grand apparitions of an epic flood; divinations of mighty yellow waves, the floating rubble of civilization, and the drowned bodies of uncounted thousands. Then the whole sea turned to blood.

A voice would appear during these fevered glimpses of the apocalypse, and it would say:

Look at it well; it is wholly real and it will be so. You cannot doubt it.

In the June of 1914, Jung had dreamt of a frightful cold that had again descended from out of the cosmos:

This dream, however, had an unexpected end. There stood a leaf-bearing tree, but without fruit (my tree of life, I thought), whose leaves had been transformed by the effects of the frost into sweet grapes full of healing juices. I plucked the grapes and gave them to a large, waiting crowd…

It was on August 1st the war broke out.

Crash.

Bang.

Wallop.

Could Jung, a creative and spiritual man, an actor in the divine drama, have suffered through the trauma of a war not yet even begun?

It sound absurd but an effect can occur before its cause. Retrocausality, the physicists call it, high weirdness on a quantum level. Theories abound of the block universe, where the past, present and future all exist together; where, if seen from above, time would be seen as spreading outward, like pooling water; British astronomer Arthur Eddington’s Arrow of Time splintered among the muck.

I once dreamt of an ancient Japanese village, high in the mountains, shrouded in the thickest mist. Out in the valley below I could hear the most terrible roars; I watched as vast and impossible shadows moved slowly behind the trembling maple trees. The dream seemed to last mere moments before I woke in a fit of confusion, in a bed in a room blacker than black.

The following day an earthquake occurred off the Pacific coast of Tōhoku in Japan. Some fifteen thousand people died that day, dwarfed by waves 133ft. high.

It had been a coincidence, I was sure; my brain making some slapdash attempt at bringing meaning to the meaningless, making a connection that had not been there. Yet I can still recall that rising nausea as I heard the news coming in over the crummy office radio, reality seeming to wash oh so gently away.

Perhaps our Gods merely like to deliver their dire warnings hidden within the chaotic symbol and metaphor which come roaring from the recesses of our unconscious mind whenever we come to a rest, a psychic wave crashing against the banks of reality.

Perhaps those wily cats, vanishing into the night, had been on to something.

*

Her antiquity in preceding and surviving succeeding tellurian generations: her nocturnal predominance: her satellitic dependence: her luminary reflection: her constancy under all her phases, rising and setting by her appointed times, waxing and waning: the forced invariability of her aspect: her indeterminate response to inaffirmative interrogation: her potency over effluent and refluent waters: her power to enamour, to mortify, to invest with beauty, to render insane, to incite to and aid delinquency: the tranquil inscrutability of her visage: the terribility of her isolated dominant resplendent propinquity: her omens of tempest and of calm: the stimulation of her light, her motion and her presence: the admonition of her craters, her arid seas, her silence: her splendour, when visible: her attraction, when invisible.

– James Joyce, Ulysses.

I imagine the moon that night, the perpetual friend of the lost and the lonesome, sagged above the land, a broken and useless talisman, an inveiglement to death and blood, a manic lust as thick as fog.

I imagine young Sergeant Werner Handorf as he eased his Junkers Ju 88 into the unapproachable splendour of the empyrea, a bewitching drone pervading his very soul (a Moonlight Sonata, perhaps), a wondrous requiem for the Luftwaffe dead.

We have arrived.

We have arrived at Adolf Hitler’s revenge.

Revenge for the cowardly attack on Munich, Handorf’s squadron commander had said, revenge for the disruption of a celebration of the Greater German Reich,

Okay, comrades, you know the outlines of our mission this evening. Together with other squadrons, we have the task of taking revenge for the English attack on Munich during the night of 8th and 9th of November. We will not respond in the same way, by bombing innocent apartment buildings, but in a way they will not be able to ignore over there. Our bombs will fall on armaments factories!

The gentlemen of the Royal Air Force attacked Munich. The Führer and our commander, the Reich Marshall, are unwilling to let even an attempt to attack the capital of the movement go unpunished. Thus our mission this evening is to destroy Coventry’s industry!

You know what that means, comrades! This city is one of the prime manufacturing sites for the enemy’s air force, and has other important factories that produce trucks and tanks. It can be said to be the center of English motor vehicle manufacturing, especially of trucks. There are also many factories that manufacture motors, motor parts, and tires. There are several factories that make aircraft motors, most notably Rolls-Royce.

You can see that the mission is worth it! If we damage this armaments center, we will have given another hard blow to Mr. Churchill’s war production! That is the purpose for our mission.

It is 1700. We take off at 2130. We will not be the first squadron to take off, but there will be enough left over for us and the comrades who follow. Tomorrow morning, the factories over there must be in ruins.

At ease until 1930, then prepare for take off. Good luck, comrades!

Werner Handorf was not a monster.

That is the great tragedy of this piece, I believe, its distinct lack of monsters. We have met fools and the foolish, the damaged and deranged but no monsters to be found. Only men who are capable of monstrous deeds.

Werner Handorf had been just another young man, from New Tempelhof in Berlin, engaged to his sweetheart (Marielies, the daughter of the owner of the colonial goods shop over on Berlin Street). Werner Handorf had served his country with honour and distinction, distinguished for his bravery over the skies of Poland and Holland and Belgium. Werner Handorf was just a another man.

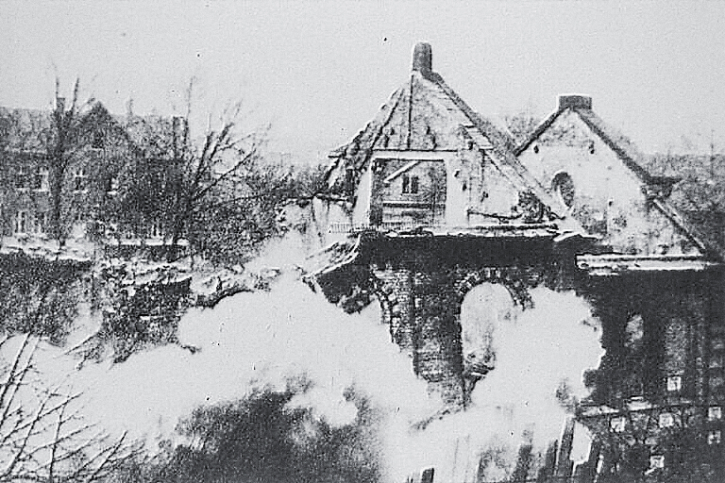

It had been early evening when the first mournful wail of the air-raid siren began its tired, desperate portent. The sky was ready to fall. Run. Run. Run.

The anti-aircraft defence team l only received their warning some ten minutes before: THE GERMANS ARE COMING! perhaps, THE GERMANS ARE COMING! and as the siren had reached its dying breath, the sky had been abloom with the ferocious glare of parachute flares as they danced in the moonlit skies.

Or so I imagine.

The incendiaries had soon began their vicious work, tireless flames jumping between the half-timbered houses and the clusters of close-knit streets with a playful frolic.

I can imagine the Central Fire Station now, inundated with call after call after call, hundreds of people feverish with terror. The city was burning after all.

The incendiaries, they must have wailed from the sky like the wrath of a biblical God. They had began to explode, an unusual behaviour. They killed and they maimed, they would burst into ferocious life with a flurry of red-hot shards of seething metal; the people unprepared for the brutality humanity inflict upon one another, over and over and over again.

Incendiaries landed upon the roof of the great St. Michael’s before uncoiling with a perverse excitement; the Provost of the cathedral, Richard Howard, and his merry band of helpers left scrambling to extinguish the many fires that had begun erupting right across the old oaken rafter.

Betty Popkiss had just left school when she joined the St. John Ambulance in Coventry. She had just left school when the Moonlight Sonata begun,

It was a frightening time – the start of saturation bombing of munitions and engineering works in Coventry. I had just become a St John Ambulance volunteer. It was my first job after leaving Barr’s Hill Girls Grammar School and that night I called into the air precaution post that stood in Hen Lane, Holbrooks. As our post was only round the corner from where we lived, I used to call in most evenings and see what was going on.

The bombing that night began with a shower of slow-burning incendiaries. We all ran around putting them out with sand and earth. A man ran up and told me one was smouldering on his roof. He asked me if we could get a ladder and go up into his loft before the house caught fire. I hated heights and was really nervous, but between us we managed to put out the flames with the help of a bucket and a stirrup pump.

Then, as I walked home, the main shelling suddenly started. It was very dark; the sirens were wailing and our anti-aircraft guns were blazing as the bombers dropped their high explosives. Suddenly, a little girl who lived on my road ran up to me and just said: Mummy, Daddy… please… Something was obviously terribly wrong and I told her to run on to the ARP post to get help while I dashed down the road.

As I ran, I looked ahead and realised a bomb had made an almost a direct hit on an Anderson shelter. As I got near, I realised our neighbours, the Worthington family, were all trapped inside. Instinctively, I started digging into the rubble with my bare hands. It was too slow to work like that and I frantically looked round for something to use. Remarkably, I found a spade lying near by. I remember hearing moans from inside. There was no shouting, no screams.

A young boy on a bike appeared in the street and as I looked up I noticed the kitchen door of the family’s house had been blown open. I shouted to him go upstairs and get some blankets but he was upset and didn’t want to go into somebody else’s house. I can still see his frightened face. I told him just go and do it then other people started arriving to help. We all worked together, fumbling around in the dark with only light from the shells exploding overhead.

Together, we got the family free. There were Mr and Mrs Worthington, their daughter Joan, who was a friend of mine, and I think two other sisters and two other girls. I helped to give them first aid. I just pulled off my brand new black coat and laid it over them. I was awarded the George Medal.

The cats had watched from their hiding place as the city lit up in a myriad of brilliant reds and lustrous oranges, liquid metal screaming through the starless heavens and into oblivion.

They soothed one another and offered consolation. All will be well, they had said, all will be well.

The sweet smell of tobacco meandered through the broiling air at the corner of Broadgate and High Street as the newsagent, Salmon & Gluckstein, went up in smoke.

A pig, hung in the window of a nearby butcher’s shop, had been cooked to perfection.

The Luftflotte 3 and the pathfinders of Kampfgruppe 100 swept across the moonlit sky releasing their vicious menagerie of high explosives, incendiaries, oil bombs and land-mines onto the embroiled streets below; Luftwaffe pilot, perhaps the young Werner Handorf from Berlin, was said to have felt his nostrils prickling, smelling the city burning some six thousand feet below him.

It was in the depths of the burning Earth where the huddled masses, cramped and bewildered in the air-raid shelters and the cathedral crypts, could do little than listen as their sweet Coventry succumbed to the incessant ferocity of the Nazis’ blitzkrieg.

Women were seen to cry, wrote the Mass Observation report in the traumatic days that had followed, to scream, to tremble all over, to faint in the street, to attack a fireman, and so on.

The Coventry & Warwickshire Hospital rocked and roared beneath the terrific onslaught of the German fleet, terrified nurses and terrified doctors forced to perform the miraculous as the world ended around them with a

CRASH

and a

BOOM

and a

POW.

The Central Fire Station was now conflagrant; the whole city, in fact, ringed with leaping flames, bathed in brilliant moonlight, a few searchlights sweeping the smoke-filled sky. It was as if all hell had been let loose that night. The constant crash of bombs preceded by that terrifying whistle as they came down, fire engine and ambulance bells ringing, folks shouting, screaming and crying and digging in the ruins, a red glow overall from the flames and the air filled with choking smoke fumes.

An abandoned tram was blown clean over a house into a nearby garden, sent heavenward by the cacophony of high explosives littering the ravaged pavements and the shattered buildings, the tram windows still intact by some nonsensical luck.

A man ran wildly through the hellish streets, pursued by a knee-high river of boiling butter like a tidal bore, a tsunami, white horses running amok from a nearby dairy.

The ambulances which had arrived from nearby Birmingham were left stalled in the streets as the ancient buildings collapsed into fiery ruin, smouldering debris and vast craters littering the devastated streets.

An inferno had engulfed the cathedral. Hope had been lost among the cancerous flames. The Solihull Fire Brigade, having finally traversed the vestiges of the once proud medieval Coventry, had arrived with little option, the hoses damaged and the water mains left fractured by the endless bombardment. Provost Howard and his tired men could do little more than remove as much as they could muster while the Wardens helped ferry those who had sought some shelter beneath.

They watched, all of them, as the flames consumed the last of St. Michael.

Father Forgive.

Father Forgive.

*

Woe, destruction, ruin, and decay; the worst is death and death will have his day.

– William Shakespeare, Richard II.

Funny story (according to the Coventry City Council website, at least): a statue of the infamous Peeping Tom, the voyeuristic tailor from the legend of Godifu, Countess of Mercia, had been found out on the ravaged streets the morning after the city burned, apparently mistaken for a charred human corpse amongst the smouldering rubble after being blown out of its niche during the raid.

Perhaps they had meant funny as in peculiar rather than the ol’ haha. I mean, imagine yourself in that situation (i.e. mistaking the badly burnt wooden statue of folkloric villain for what had once been a living, breathing human being) and the story becomes a whole lot less funny. But perhaps this is the way of the world: LAUGH OR BE DAMNED FOR ALL ETERNITY.

King George VI was said to have sobbed amongst the ruins of Coventry Cathedral, two days after the Moonlight Sonata had reached its tragic coda, his whole attitude one of intense sympathy and grief.

Grief.

Grief.

Grief.

Our lives are spent running from the clutches of grief, recoiling from the anger and the denial and the ardent depression, and yet it threatens to consume us far more than we care to admit. The fear of grief haunts us in our quietest moments, lurking amongst the darkness when sleep seems but a dream.

Just imagine those who had awoken to a city coventrated. Just imagine waking up to a world where your home had become a byword for utter annihilation.

I would imagine it to be akin to waking on Vulcan or Narnia, or in Dante’s Nine circles of Hell, through me you go to the grief wracked city. Just imagine the once prominent medieval architecture of your beloved hometown hanging precariously over the bloodied and burnt remains of friends and of neighbours, scattered amid smouldering rubble.

Denial is our first defence against the behemothic tides of grief but that denial cannot last, one day, the universe will collapse into entropy, and even Shakespeare and Coca Cola won’t be remembered. Death and decay can be denied no more than we can deny the phases of the moon and yet we persevere under the illusion that all will be well, disregarding controlled demolitions across a devastated city and mass funerals at the London Road cemetery.

The cultural anthropologist and writer Ernest Becker astutely summed it up in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book The Denial of Death,

The irony of man’s condition is that the deepest need is to be free of the anxiety of death and annihilation; but it is life itself which awakens it, and so we must shrink from being fully alive.